Jewellery throughout time – Medieval jewellery making

Europe became more important for the innovation of the jewellery industry after the fall of the ancient civilizations in Egypt, the Middle-East and the Roman Empire, although it took quite some time before European civilizations really established that important role and position. Nearly a thousand years passed by before new knowledge and ideas were enabled and applied to jewellery making in Europe.

More contact and interactions with distant civilizations became possible due to, for instance, the Crusades. The expansion of trade and commerce and the flowing of wealth from royalty, the church and nobility to a larger middle class made it possible for more people to afford jewellery. However, this also created a situation in which the nobility and upper classes were determined to distinguish themselves from the masses by putting up Sumptuary Laws in the 13th century. These Sumptuary Laws were an attempt to regulate consumption and to restrict personal expenditures with regards to extravagance and luxury. Through these laws social hierarchies and morals could be regulated and reinforced through the restrictions that were put in place, which often depended upon a person’s social rank. This basically meant that they capped luxury in for example items such as dress and jewellery for middle and lower class people. The Sumptuary Laws forbade yeomen and artisans from wearing gold and silver, hence making sumptuous clothing and jewellery styles a privilege to just the higher ranks of society. While precious gems, gold and silver were exclusively worn by royalty, nobility and people from the church, the people of lower status, the so-called commoners, usually wore base metals, such as copper and bronze.

More contact and interactions with distant civilizations became possible due to, for instance, the Crusades. The expansion of trade and commerce and the flowing of wealth from royalty, the church and nobility to a larger middle class made it possible for more people to afford jewellery. However, this also created a situation in which the nobility and upper classes were determined to distinguish themselves from the masses by putting up Sumptuary Laws in the 13th century. These Sumptuary Laws were an attempt to regulate consumption and to restrict personal expenditures with regards to extravagance and luxury. Through these laws social hierarchies and morals could be regulated and reinforced through the restrictions that were put in place, which often depended upon a person’s social rank. This basically meant that they capped luxury in for example items such as dress and jewellery for middle and lower class people. The Sumptuary Laws forbade yeomen and artisans from wearing gold and silver, hence making sumptuous clothing and jewellery styles a privilege to just the higher ranks of society. While precious gems, gold and silver were exclusively worn by royalty, nobility and people from the church, the people of lower status, the so-called commoners, usually wore base metals, such as copper and bronze.

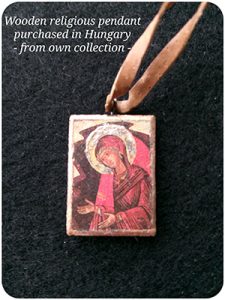

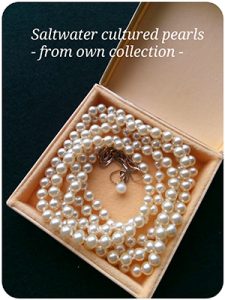

During the Renaissance a vast expansion of technology, exploration and knowledge had a significant effect on the development of jewellery manufacturing in Europe. There was an increased availability of fine gems and precious metals, as well as a greater exposure to the designs of jewellery from other, distant cultures. Besides, the skills to make excellent fake jewellery with imitation gems became better and more sophisticated. While people weren’t able to jewel-cut in early Modern Era, the jewel cutting abilities improved during the Renaissance and more elaborate designs were created. Also, the ancient art of engraving gems revived and religion was more imbedded into the designs. This period showed an increasing dominance of the use of gemstones. For instance, during the 17th century is was very fashionable to wear pearls in abundance. A Parisian bead maker of the 17th century, called Jaquin, is believed to have invented and patented the first faux pearl technique by coating the inside of blown glass spheres with a mixture of varnish and iridescent ground fish scales and then filling them with wax to strengthen them. Actually, just about any kind of fake gem could be produced during this time.

Poison rings came into fashion during the 16th century, taken from Ancient Greek origin, and also lockets and rings containing perfume, locks of hair or pictures were popular items. The 17th century was an important moment in the history of jewellery manufacturing, since for the first time it saw fashion go together with accessories. Dark clothing styles were associated with gold jewellery, whereas pastels and white clothing styles were combined with silver, pearls and gemstones. When Napoleon Bonaparte became emperor of France in 1804, he brought the grandeur of fashion and jewellery back to court. Jewellers introduced so-called “parures” under his rule; matching sets of jewellery. Napoleon was a great lover of diamonds and also resurrected the trend of wearing cameos, engraved jewellery pieces featuring a raised relief image, which were already made in Greece during the 3rd century BC, which soon became popular jewellery items. A division started existing between the different sorts of fine metal workers: so-called “joailliers” worked only fine jewellery pieces with precious metals and expensive gemstones, such as gold, silver, real pearls and diamonds, whereas “bijoutiers” crafted jewellery with less precious materials and gems. These new terms were used to differentiate the arts of jewellery making and this practice continues to this day, although the distinction is not as strict anymore as during those times.

Poison rings came into fashion during the 16th century, taken from Ancient Greek origin, and also lockets and rings containing perfume, locks of hair or pictures were popular items. The 17th century was an important moment in the history of jewellery manufacturing, since for the first time it saw fashion go together with accessories. Dark clothing styles were associated with gold jewellery, whereas pastels and white clothing styles were combined with silver, pearls and gemstones. When Napoleon Bonaparte became emperor of France in 1804, he brought the grandeur of fashion and jewellery back to court. Jewellers introduced so-called “parures” under his rule; matching sets of jewellery. Napoleon was a great lover of diamonds and also resurrected the trend of wearing cameos, engraved jewellery pieces featuring a raised relief image, which were already made in Greece during the 3rd century BC, which soon became popular jewellery items. A division started existing between the different sorts of fine metal workers: so-called “joailliers” worked only fine jewellery pieces with precious metals and expensive gemstones, such as gold, silver, real pearls and diamonds, whereas “bijoutiers” crafted jewellery with less precious materials and gems. These new terms were used to differentiate the arts of jewellery making and this practice continues to this day, although the distinction is not as strict anymore as during those times.

The Romanticism of the late 18th century had a profound impact on how jewellery manufacture developed in the West. The start of modern archaeology and the public’s fascination with the discovered treasures of the past combined with a growing interest with medieval and Renaissance arts became significant influences in the development of jewellery designs. Also, changing social conditions and the start of the Industrial Revolution resulted in a growing middle class. This group of middle class people had both the desire and the means to buy jewellery for themselves. This period showed the appearance and disappearance of many styles, some new and original, others based on ancient designs which were found in the ruins of long gone civilizations, such as the Egyptians, the Greek and the Romans. A very unique sort of jewellery that came into fashion during the Romanticism, originating in England, was the so-called “Mourning Jewellery”. When Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, died in 1861, she was often seen wearing mourning jewellery. These pieces allowed the wearer to continue wearing jewellery while at the same time expressing their mourning over the death of a beloved person. This type of jewellery also highlights how sentimental the Victorian Age was. Mourning Jewellery was mostly crafted with jet gemstones from Whitby, a type of lignite and precursor to coal, although other types of black materials were also used, and often these items contained a lock of hair of the deceased person.

The period of the Romanticism also entailed the first major collaboration between the East and the West regarding jewellery manufacturing, e.g. between artists from German and Japan, who made shakudō plaques set into filigree frames for the Stoeffler firm in 1885. Shakudō is an alloy of copper and a small amount of gold (between 2% and 7%) and is also known as “red copper”. Modern production studios arose with the founding of jewellery companies such as Tiffany & Co. (USA, 1837), Cartier SA (France, 1847) and Bulgari (Italy, 1884), which were completely new developments in comparison with the dominance of individual craftsmen up to these times.

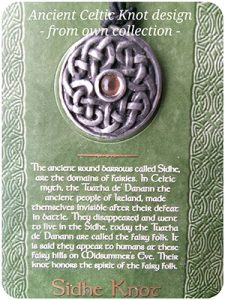

During the 18th century many whimsical fashions were introduced and at the end of the century a new design philosophy emerged as a reaction to the mass produced goods and inferior products made by machines. Leaders of the aesthetic Arts and Crafts Movement, which started in England around 1860 and was inspired by the ideas of architect Augustus Pugin, writer John Ruskin and designer William Morris, wanted handcrafted jewellery to be brought back into fashion as opposed to using machinery for creating jewellery. The followers of the Arts and Crafts Movement promoted simple arts and crafts, based on floral, primitive and Celtic designs and forms and with the use of less precious metals and expensive stones. Instead, silver, copper and brass were used to create jewellery. Polished stones, which were used in Arts and Crafts craftsmanship, gave a more gentle, medieval and handmade look of an individual nature to the handcrafted designs. The focus was aimed on the artistic elements and the beauty of the design. By the 1900s the movement was kind of replaced by a more ostentatious version, which started in France: Art Nouveau (≈ 1890-1910), although its ideas of reacting against machine production were still visible throughout these new characteristics of jewellery making.

During the 18th century many whimsical fashions were introduced and at the end of the century a new design philosophy emerged as a reaction to the mass produced goods and inferior products made by machines. Leaders of the aesthetic Arts and Crafts Movement, which started in England around 1860 and was inspired by the ideas of architect Augustus Pugin, writer John Ruskin and designer William Morris, wanted handcrafted jewellery to be brought back into fashion as opposed to using machinery for creating jewellery. The followers of the Arts and Crafts Movement promoted simple arts and crafts, based on floral, primitive and Celtic designs and forms and with the use of less precious metals and expensive stones. Instead, silver, copper and brass were used to create jewellery. Polished stones, which were used in Arts and Crafts craftsmanship, gave a more gentle, medieval and handmade look of an individual nature to the handcrafted designs. The focus was aimed on the artistic elements and the beauty of the design. By the 1900s the movement was kind of replaced by a more ostentatious version, which started in France: Art Nouveau (≈ 1890-1910), although its ideas of reacting against machine production were still visible throughout these new characteristics of jewellery making.

Art Nouveau jewellery encompassed the curving, organic lines of romantic, female forms, flowers, animals, birds and colourful imaginary dreaminess. It defined a notable and stylistic revolution to the jewellery industry and was closely related to the German Jugendstil. Art Nouveau jewellery makers, such as the famous René Jules Lalique, tried to create a memorable effect or design. They focussed on symbolic work, including eroticism and death. Twentieth century jewellery was still a status symbol, but at a much more affordable price for the middle class market. Materials such as glass, enamel and horn, as well as metal alloy and imitation stones were used to replace the more expensive gold and silver to create beautiful and artistic jewellery pieces, that at the same time emphasized the previously neglected visual and tactile qualities of these new materials.

The end of World War I ushered a change into a more sober style of jewellery manufacture. Growing political tensions and the after-effects of the war incited a more modest style as a reaction against the perceived decadence of the turn of the century. It led to simpler forms of designs, combined with more effective mass-production of high-quality jewellery. During these years French designer René Lalique, for instance, became a leading example of good mass-produced glass jewellery. This style, in between 1920-1930, is popularly known as Art Deco. The German Bauhaus movement, that fits in this style category, had the following philosophy about this period: “No barriers between artists and craftsmen.” It led to some interesting and stylish simple forms and shapes and the jewellery created during these years is sometimes also referred to as “cocktail jewellery”. Cocktail jewellery was greatly influenced by famous designers, such as Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, who both used costume jewellery and mixed it with genuine gems and expensive fine jewellery.

The production of fine jewellery stagnated during World War II because of the rationing of metals. Fine precious metals and gem jewellery were practically not available, but quality costume jewellery from America became a great alternative. During the 1940s and 1950s the influence of the (North) American culture was quite dominant in Europe and costume jewellery was a visible example of this fact. Since the 1960s there has been a fairly constant redefining of contemporary jewellery design and innovations on jewellery making. Non-metals have been introduced to more modern jewellery creations and the concept of wearable art has widened. There is a clear increase of variety in the different styles of jewellery manufacture development. These developments have made it possible for a much larger segment of the population to buy jewellery and also for a growing number of creative people to craft jewellery, sometimes with unique and personalized designs. Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder and when looking at all the jewellery innovations, you can definitely see this put to practice throughout time. Nowadays artisan jewellery grows both as a hobby and as a profession. Gwendolyne’s Steampunk Gems is a great example of an artisan jeweller, who incorporates traditional workmanship and techniques with both modern and precious materials to handcraft classy and beautiful adornments in Steampunk style.

The production of fine jewellery stagnated during World War II because of the rationing of metals. Fine precious metals and gem jewellery were practically not available, but quality costume jewellery from America became a great alternative. During the 1940s and 1950s the influence of the (North) American culture was quite dominant in Europe and costume jewellery was a visible example of this fact. Since the 1960s there has been a fairly constant redefining of contemporary jewellery design and innovations on jewellery making. Non-metals have been introduced to more modern jewellery creations and the concept of wearable art has widened. There is a clear increase of variety in the different styles of jewellery manufacture development. These developments have made it possible for a much larger segment of the population to buy jewellery and also for a growing number of creative people to craft jewellery, sometimes with unique and personalized designs. Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder and when looking at all the jewellery innovations, you can definitely see this put to practice throughout time. Nowadays artisan jewellery grows both as a hobby and as a profession. Gwendolyne’s Steampunk Gems is a great example of an artisan jeweller, who incorporates traditional workmanship and techniques with both modern and precious materials to handcraft classy and beautiful adornments in Steampunk style.

One thing can be stated for sure: jewels and jewellery will forever remain an integral part of humanity and a lovely part in my opinion.

Gwendolyne Blaney – GSG

References

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewellery – “Jewellery”

History of Jewelry – http://www.historyofjewelry.net/ – “History of Jewelry – All about Jewellery”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/art/jewelry/The-history-of-jewelry-design – “The History of Jewelry Design”

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumptuary_law – “Sumptuary law”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/topic/sumptuary-law – “Sumptuary law”

Antique Jewelry Investor – http://www.antique-jewelry-investor.com/identifying-cultured-pearls.html – “Identifying Cultured Pearls”

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cameo_(carving) – “Cameo (carving)”

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jet_%28lignite%29 – “Jet (lignite)”

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arts_and_Crafts_movement – “Arts and Crafts Movement”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/art/Arts-and-Crafts-movement – “Arts and Crafts Movement – British and International Movement”

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Nouveau – “Art Nouveau”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/art/Jugendstil – “Jugenstil – Artistic Style”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/art/Art-Nouveau – “Art Nouveau – Artistic Style”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rene-Lalique – “Rene Lalique”

Encyclopædia Britannica – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alphonse-Mucha – “Alphonse Mucha”

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_jewelry – “Art jewelry”

Pauline Weston Thomas – https://www.fashion-era.com/jewellery.htm – “Fine and Fake Jewellery”

Cooksongold/The Bench – https://www.cooksongold.com/blog/trends-and-inspiration/a-history-of-jewellery – “A History of Jewellery”